Return To Føroyar

10 October 2016

The North Atlantic Arc Home

| Octoberrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

|

|

Monday 10 October 2016--My flight is late this afternoon, so there is time

this morning for some last-minute shopping in town, followed by a visit to Føroya

Fornminnissavn, the National Museum of the Faroe Islands. Curiously, the

museum is tucked into a small business park in the suburb of Hoyvík, just north

of Tórshavn's ring road. It's not very large, but nevertheless manages to cover a

broad range of subjects in Føroyar's natural and human history. There are

fishing artifacts, whale skeletons, Faroese knitting patterns, household and

industrial items, examples of clothing through the centuries, geological exhibits,

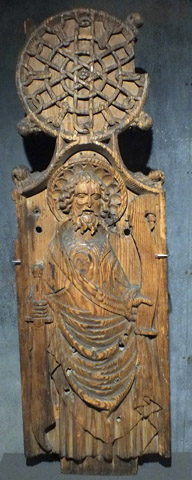

mounted fauna, and so on. The museum's prize possessions are 15th-century

carved wooden pew ends from St Olaf's Church in Kirkjubøur.* These were

removed during a refurbishment in the 19th century, and for a hundred years

were housed in a museum in Copenhagen, to the great chagrin of the Faroese.

They were finally repatriated, along with other antiquities, in 2002. This is a

struggle I've witnessed in many of the more remote places I've visited. A notable

example is the Lewis Chessmen, most of which are in the British Museum in

London. Eleven are in the museum in Edinburgh. They are, of course,

accessible to a large number of people in these places, as the pew ends were in

Copenhagen. The folk of Lewis, naturally, feel a moral imperative to bring the

artifacts "home" (never mind that they, like the pew ends, were likely made in

Norway). As important, or perhaps more so, such artifacts can be a draw for

tourists to visit such far-flung places. Fortunately, there are many Lewis

chessmen, and it isn't a strain for the British Museum to make a long-term loan

of a number of pieces to the Museum nan Eilean in Stornoway, as well as

touring a collection around various museums in Scotland. There is no happy

compromise in most other cases. I recall, for example, seeing a replica of a carved

stone cross in Barra, with an explanatory note that indicated that the locals

were quite peeved not to have the original. The Faroese are fortunate, I guess,

that the Danes eventually agreed to return the entire set of pew ends. I feel

likewise fortunate to see them here as the crown jewels of the museum's

collection, rather than as a colonial oddity in a museum in Copenhagen.

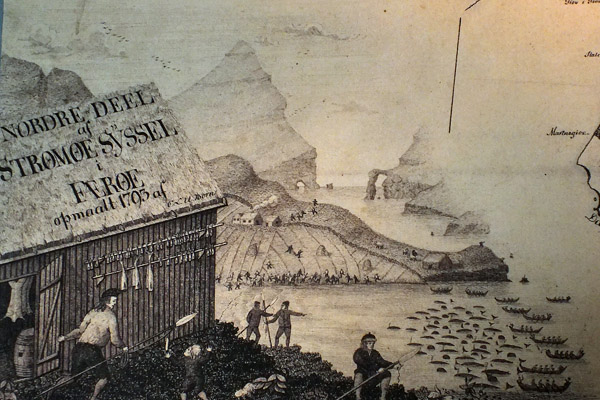

One of the old prints on display depicts the grindadráp, the pilot whale hunt that, infamously, goes on to this day. Thanks to internet memes, this is probably the only reason many people have ever heard of the Faroe Islands. When a pod of whales is spotted offshore, Faroese fishermen head out in their boats to herd them into one of the narrow fjords, where they are slaughtered. Dramatic photos of whales thrashing in the scarlet waters of the killing bay readily fuel the outrage of those who oppose the hunt. Accompanying these photos is inflammatory text depicting the Faroese as bloodthirsty savages engaged in ritual murder. I have mixed feelings on the matter. I have friends who are vegan, and oppose all forms of animal exploitation. I might think that a bit naive, but I can respect it from a moral standpoint. But those of us who buy our hamburger out of a cooler in the grocery, without giving a thought to the slaughterhouse, are perhaps a bit hypocritical in our outrage. I've learned that the grindadráp is quite strictly regulated, with tools and methods carefully prescribed. The whale meat is distributed among the community according to a legal formula, and it makes up about thirty per cent of the household dietary protein. I understand that people don't like to see this sort of thing, but it seems to me that there is, among most of the protesters, a lack of appreciation for what it's like to live on a rock in the middle of the North Atlantic. Føroyar has changed a lot in the past century, with vastly improved transportation and communication bringing it closer to the outside world, and high tech helping to transform the economy. But at its heart, it remains a country of fishermen and sheep farmers. The Faroese live a lot closer to the edge of civilization than most of us, in more ways than one. I leave Tórshavn behind, passing through the tunnel out of town one last time, then the undersea one to Vágar. Drive past the airport and along Sørvágsfjørður to the end of the road. In 2001, the road ended at the foot of a mountain ridge, which I walked up over to peer down on the isolated village of Gásadalur. There is a tunnel now, and I park in the village itself and go for a short walk to see Mulafossur, perhaps Føroyar's most picturesque waterfall. Before the tunnel, access was either by helicopter, or by boat to the precarious landing at the foot of the cliffs, or by foot over the mountain. Back up among the houses, I'm approached by a border collie, who, eager to play, drops his toy at my feet. His toy is a chunk of gravel. How pathetic...I play with him a while before leaving, making a mental note to bring a tennis ball with me if I ever return. I make a short stop in Bøur, nestled below the road along the shore of Sørvágsfjørður. Fuel up the car in Miðvágur, turn it in at the airport, and check in for my flight to Edinburgh. It's been overcast and misty all day, a wet gray bookend to the day I arrived, a good day to say goodbye. I've had pretty good luck with the weather in between. The flight is a little more than an hour. About halfway along, I find myself looking down at Sula Sgeir, a rocky islet about forty miles north of Lewis. This is the site of another traditional hunt, one that goes back five centuries or more. Every August, a handful of men from the village of Ness, at the northern tip of Lewis, make the daunting crossing to spend two weeks harvesting guga, or fledgling gannets. It's the last hunt of its kind still permitted in the European Union. Like the grindadráp, it's regulated--there is a limit of 2,000 birds, an easily sustainable harvest--and like the grindadráp, it arouses protest. The taste for guga back in Lewis is part of what drives the hunt, but the men who participate also speak of a passionate desire to preserve tradition and a rapidly disappearing way of life. I'll never witness the guga hunt, nor am I likely to see the grindadráp...I'm just a tourist passing through, with but the barest inkling of what these places and people are really like. I feel the conflicting impulses of thinking on the one hand that these kinds of hunts have no place in the modern world, and on the other that outsiders have no business telling these islanders how to live their lives. Would the outside world look differently on these activities if they were being conducted by "aboriginal peoples" trying to maintain a traditional lifestyle? Is there really any difference? I have no answer. Modern civilization will overtake these people soon enough, I suppose. Or perhaps one day it will collapse, and folk like this will be the only ones who know how to fend for themselves. In the meantime, tourists like me will come, and gawk, and ponder. Next *As noted earlier, these were most likely actually commissioned for the cathedral in Kirkjubøur, and moved to St Olaf's Church after the cathedral was deconsecrated during the Reformation. |

|

The Neighborhood

|

Geology Of Tjørnuvík

|

Landslide in Klaksvík

|

Grindadráp

|

Auk!

|

Pilot And Killer Whales

|

Tórshavn

|

Pew Ends

|

Pew Ends

|

|

|

|

|

|

St Bartholomew, St James, St Judas Thaddeus, St Peter, Unidentified, Unidentified

|

|

|

|

|

|

Madonna And Child, St John The Baptist, St Paul, St Matthew, St Andrew, St Thomas

|

Medieval Burial

|

Modern Interpretations Of Traditional Dress

|

Faroese Knitting Patterns

|

Boats And Sheds

|

Leaving Tórshavn

|

Sørvágsfjørður

|

Trailhead

The trail to Gásadalur that I walked in 2001 ascends along the edge of the cliff at left

|

Gásadalur 2001

|

Gásadalur

|

Gásadalur

|

Gásadalur

|

Gásadalur

|

Gásadalur

|

Airport Lights Above Sørvágur

|

Bøur

|

Bøur

|

Bøur 2001

|

Bøur

|

Miðvágur

|

Atlantic Airways

|

Away

|

Sula Sgeir

|

Approaching Edinburgh

|

Queensferry

|

The Ferry Tap

|

The Ferry Tap

|

Queensferry

|

The Forth Bridge

Next

| Octoberrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

The North Atlantic Arc Home

Mr Tattie Heid's Mileage

Results may vary