Six Ways To Fundy

18 May 2022

The North Atlantic Arc Home

| May |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 |

|

|

Wednesday 18 May 2022--I'm headed to Moncton, New Brunswick today, an

hour and a quarter if I go direct, but I have things to see on a very indirect route.

I start by driving out the dead-end road to West Bay. There are views from

here of the tip of Cape Split, the deeply-cleft cliffs showing the origin of the

name. There's also a view of Partridge Island, at one time the site of the

settlement that eventually became Parrsboro. There's a local legend, similar to

the story of Farmer in the Magdalen Islands, about a man from Partridge Island

who sold a horse to someone on Cape Blomidon. It's four miles across the

Minas Passage, but the fellow carted the horse overland, 150 miles around the

Minas Basin. When he got back home, the horse was waiting for him, having

swum across the channel. The story goes that the man made the overland trek

again to give the buyer his money back.

Back through Parrsboro, then west, about thirty miles to Advocate Harbour. The name is pronounced like the verb, rather than the noun, with a long a. There's a pebbly beach here, backed by a seawall, which, along with dikes by the harbor itself, polderize the marshes behind. For some reason, the seawall has a vast accumulation of driftwood atop it. The fact that the road running behind it is called Driftwood Lane suggests that this is the normal state of things. The entrance to Cape Chignecto Provincial Park is just west of town. There's an interpretation center--not open yet--and a short walk down to a beach, from which can be seen the rugged headland jutting southwest into Fundy, dividing Chignecto Bay from the Minas Channel. Kayaking along the 600-foot cliffs and sea caves is the major activity here. (I suppose it's trees dropping off the eroding cliffs that wash up at Advocate Harbour.) The park has backcountry camping along its miles of trails. Three days is suggested for the full loop, which will take the hiker past abandoned farmland and logging camps, and scant remains of the ghost towns of Eatonville and New Yarmouth. There's a day use area at the north end of the park, with a couple of easy trails leading to scenic overlooks, more my speed. It'll have to wait for another visit. Route 209 leads north, east of the park, and then along the coast of Chignecto Bay. Three-quarters of an hour along, I come to the Joggins Fossil Centre, above the Joggins Fossil Cliffs. This is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, famous for its abundance of fossils from an ancient rainforest, exposed by the eroding cliffs along the shore. Charles Lyell, considered the father of modern geology, visited Joggins in 1842 and 1852, and apparently the fossil record here is cited in Darwin's On the Origins of Species, although it's unclear to me whether he ever visited. I have a good look around the Centre, and then go halfway down the stairs to look at the cliffs. I have unfortunately arrived at high tide, so a walk on the beach is not possible. Another thing to come back for. I have lunch at McPuffin's, just up the street, and then drive up through the town of Amherst, one of many named for our old pal Lord Jeff, whose reputation in the 18th century was obviously much better than it is today. One of the bus tours I drove had instructions to turn the passengers loose for lunch here, but the place was pretty dire, so we found other accommodation eventually. It doesn't look quite so bad today, but I don't feel any urge to stop. West of town, down a side road just this side of the New Brunswick border, I find the Beaubassin and Fort Lawrence National Historic Sites. Beaubassin was a prosperous and important Acadian village, a vital transportation link between Québec and Louisbourg. With British troops threatening in 1750, the Acadians abandoned and burned Beaubassin and other villages in the area, so that the British could not occupy them. The French built Fort Beauséjour (which I visited in 2012) across the marsh, hoping to hold the disputed border at the Missaguash River, which today marks the border between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The Brits countered with Fort Lawrence, capturing Beauséjour in 1755, and subsequently commencing the Acadian Deportation. There have been substantial archaeological digs here, but there is nothing visible of either the village or the fort today; nevertheless, the site is evocative, with its view across the marshes. The interpretation panels help the visitor to understand what once was here. I get on the highway and drive the short distance across the New Brunswick border, then turn north toward the village of Baie Verte, where I stop at the cemetery to pay my respects to Benjamin Allen, my great-great-great-great- great grandfather (previously found in 2012). If I am correct in believing that he took a land grant here after serving under Wolfe at Québec, then he was here before the Loyalists, and before even the New England Planters, recruited to populate deserted Acadian farms.* Take the coast road up to Bayfield, where I visit great-great-great-great grandparents George and Charlotte Letitia Thompson Allen, the latter a daughter of the Yorkshire incomers. Pass by the Confederation Bridge leading to Prince Edward Island, resisting the urge to cross, and continue along the Acadian shore, through Cap-Pelé, hometown of the late big league pitcher Rhéal Cormier. Pass through Shediac, then hop onto highway 16. Arrive in Moncton, find my hotel, and check in. I've passed by this city of 80,000, the largest in New Brunswick, many times, but this is my first chance to stay and have a look around. Dinner this evening is in the Tide & Boar Gastropub, followed by a couple of pints at Happy Craft Brewing. Next *Some months later, I find myself rethinking Benjamin Allen. For one thing, looking at the photo of his headstone, it occurs to me that the base it's set in might not be original. The stone's placement in the yard has always seemed odd to me, too. Referring to W M Burns' A History and Story of Botsford, published in 1933, I note that Ben's "mortal remains lie in the old churchyard" in Baie Verte. I don't know where the old churchyard is, or was; maybe this cemetery is it, or maybe not. Possibly the stone, if not Ben himself, was moved, because the old church was demolished, or the land repurposed. Burns also says that Ben was a Scot living in New England before the French & Indian War, and returned there after. I've discounted this because he goes on to say that Ben returned north as a Loyalist in the wake of the American Revolution, in 1783, and that is almost certainly untrue; he was married in what is now New Brunswick in 1771, and all of his children were born there. I've assumed that he was from Scotland, and the New England connection was the result of confusion with a contemporary Benjamin Allen born in Connecticut, who pops up spuriously in a lot of the online genealogies I see. But it seems very possible to me now that Benjamin Allen was in fact from New England and returned there after the war, only to go back north as one of the New England Planters. It's a path well documented in other cases, like that of Jonathan Eddy. More research needed. |

Parrsboro To Moncton

|

Cape Split From West Bay

|

West Bay Christ Church

|

Cape Split

|

Cape Split

|

Cape Split

|

Partridge Island And Cape Blomidon

|

Cape Split From Port Greville

|

Driftwood Lane, Advocate Harbour

|

View To Cape Chignecto

|

West Advocate

|

Cape Chignecto Provincial Park

|

Beach

|

Red Rocks

|

Joggins Fossil Centre

|

Joggins Fossil Centre

|

Joggins Fossil Cliffs

|

McPuffin's Atlantic Seafood Restaurant

|

Fort Beauséjour From Fort Lawrence

|

Beaubassin

|

Crossing Tantramar

|

The House At The End Of The Road

|

New Brunswick Border

|

Baie Verte Cemetery

|

Shy Ben

|

Cape Tormentine

|

Confederation Bridge

|

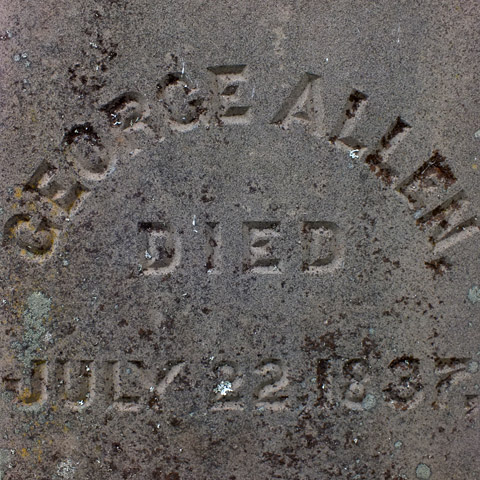

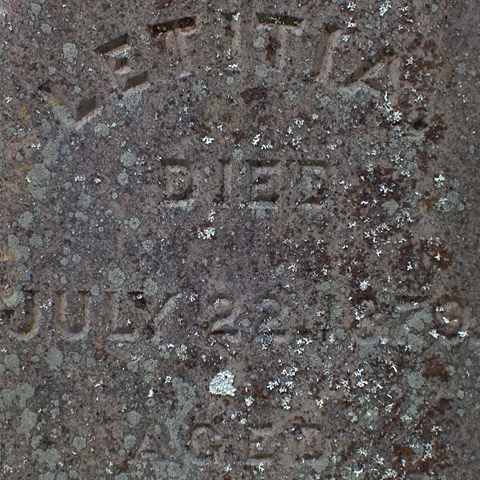

Bayfield Cemetery

|

|

|

George & Letitia

Next

| May |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 |

The North Atlantic Arc Home

Mr Tattie Heid's Mileage

Results may vary

MrTattieHeid1954@gmail.com