The North Atlantic Arc Home

| September | /Octoberrrrrrrrrrrr |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 |

|

Thursday 29

September 2005The BestIt s funny how a certain expression, saying, or even joke that you ve never heard before, or not in a long time, will suddenly crop up several times in short order. Three or four times in the past few days, in both Shetland and in Craigellachie, I ve heard someone ask someone else what the best , or their favorite , malt is, and the answer come back a free one or one someone else buys . This morning I set out to visit Balvenie. The tour is reputed to be fairly intensive (for a 20 fee, it had better be!), and they suggest you arrange transportation to and from, rather than drive, so, at the suggestion of my landlady, I take the bus. Looking at the timetable, I note that the service is very good, and it would be easy to visit quite a few distilleries this way. Aberlour next year, I think. I arrive at the Glenfiddich visitor center Glenfiddich, Balvenie, and Kininvie are all on the same grounds and we wait a bit for someone who called yesterday about the tour, but who does not show. It s just Tom, the guide, and I, then. He drives me over to the Balvenie corner of the property and tells me something of the history of the company, which is independently owned by the Grant family. (The very same can be said of Glenfarclas, but they are different Grants.) First, we visit the floor maltings. Upstairs are small mountains of Optic and Chalice, and at the end of the room are two steeping tanks end to end, maybe twelve or fifteen feet long, six or eight feet wide, and a couple feet deep. These are filled about a foot deep with grain, which is then covered to a depth of six inches or so with water at ambient temperature. In a couple days, the grain will have absorbed all of the water, and it will then be pushed through holes in the bottom of the tank to the floor below. At one point, I get to thinking about how much land will produce how much whisky, and I ask Tom about yield per acre. He doesn t know, but calls his father, a farmer, on his cell phone, and gets the answer. I wish I could remember, for your benefit, the math we worked out, and I hesitate to give a ballpark figure based on hazy recollection; I seem to recall a figure of four bottles or so an acre, but I can t swear to it. Anyway, I was impressed by Tom s efforts to satisfy my question. Downstairs, we see the malt spread out on the floor, and chat with the two men who are charged with turning it to keep it from getting too warm. There is a machine that looks a bit like a snowblower for the job, and it is pulled along a cable, making their work far less back-breaking than the old method of using wooden shovels. Still, it is very labor-intensive. Malting is not done in the summer, as it is too warm, and Balvenie will not run tours in the summer months for that reason. Next we see the mash house, which houses two stainless steel mash tuns; the larger is Kininvie s. Kininvie s product is intended entirely for blending, and I suspect that one of the reasons for building it separate from Glenfiddich is to vat the product headed for the blenders so that none will end up in the hands of brokers and subsequently appear as IB s of Glenfiddich (or Kininvie, for that matter). But I wonder, wouldn t many of us be interested in an IB of vatted Glenfiddich/Kininvie, anyway? No matter, they are obviously very careful not to let this happen. Then the stillhouse. This and the mash house are essentially like any stillhouse and mash house on any tour you ve ever been on, but of course the stillhouse is, visually, the centerpiece of any tour. Tom remarks that everyone s face lights up when they step into the room, and mine is no exception. I do my best to take some passable photos. Tom wants to get us through the cooperage before the workers there take their lunch break, so that s next. Safety glasses are mandatory, as are ear plugs it s a very noisy place. It s quite a large, one-room building, where I see barrels being broken down, others being reassembled, and all manner of repair work. A cooper pounds the barrel top into place, stuffs the cracks with a length of reed, and tightens the hoops. Another puts an old, tired cask on a machine that scrapes out the inside, then on another that rechars it with an alarming blast of flame. I am too slow to get a photo. I look inside the finished barrel; the new char looks more like a light toasting. It will be good for one, possibly two more fills. Outside is a vast yard with endless stacks of empty bourbon barrels, sherry butts, port pipes, and no small number of unidentifiable oddball vessels of various dimensions. I ask Tom about the standard practice of rebuilding 200-litre bourbon barrels into 250-litre hogsheads; he says Balvenie no longer does it. Into the warehouse. We see barrels ranging in age from a few years old to forty and more. Tom pulls the bung on a barrel of 1967 vintage and invites me to stick my nose in it. It smells absolutely wonderful, but to be quite honest, if you have a bottle of 15yo Single Barrel, you can experience very similar. Of course, you won t be standing in a dark, damp Balvenie warehouse with your hands resting on a dusty barrel full of thirty-eight-year-old whisky, surrounded by hundreds of like casks. Now, every time I open my bottle of the 15, I will be. All that s left is the tasting. Tom takes me to a room in a small building that was once the distillery manager s office. There he pours us each full drams of the Founder s Reserve 10, DoubleWood 12, Single Barrel 15, PortWood 21, and the Thirty, in Glencairn glasses. He puts his hand over the top of a glass and gives it a vigorous shake; I follow suit and note the exponential intensification of the nose (after licking the excess from my palm). He does not rush me, talks me through each dram, and gives me plenty of time to enjoy every last millilitre. I experiment a bit with water, but I ve never really liked using it, and when it comes to the Thirty, I add not a drop. It is intense, deep, complex; Balvenie cubed. I linger over it for some time, and when I lament that I cannot afford a bottle of this sublime malt, Tom produces a 3cl mini of it for me to take home. The tour started at 10:00, and it is well after 1:00 when Tom drops me at the distillery shop. I buy a few things, including a 3 x 20cl box of 10, 12, and 25. Buzzing warmly and wearing a wide grin, I walk ten minutes up the hill to Dufftown, where I have lunch, spend some time online at the library, and browse a few shops. Late in the afternoon, I catch the bus back to Craigellachie. Dinner is at the Highlander. The Connoisseur s Choice dram of Brora I have after seems watery and weak. Over at the Quaich Bar, I decide, perhaps unwisely, to have another dram of the OMC Brora I d had the night before. It s very nice, but doesn t strike me as well as it did the first time. Back at the Highlander, I enjoy my last pints and drams in Craigellachie. Oh, one other thing for some reason, no one at Balvenie ever asked me for my 20, automatically making it my favorite distillery tour of all time! Well, you know, it was by far the best, anyway. Next |

|

Balvenie!

|

The malting floor at Balvenie. After soaking in water, the barley is spread on the floor, where it begins to sprout. The temperature

must be carefully monitored, and the barley turned periodically to keep it from getting too warm. (I am accustomed to landscape

photography and use rather low-speed film, so I hope you'll forgive me if a lot of these indoor shots are a bit...heh heh...grainy.)

|

Balvenie's kiln. When the barley reaches the optimum level of fermentable sugars, it is spread on a perforated floor

above the fire and dried to arrest growth. Coal is used for drying; they say it is virtually smokeless. They used to pile peat

on top of the coal for a bit of smoke, but now burn the peat in a side stove (not seen here) for greater control.

|

Balvenie's Porteus mill. The dried malt is ground to prepare it for mashing. The mill is often the oldest piece of equipment

in a distillery--they run forever with little maintenance. So well did Porteus build their mills that they went out of business.

New distilleries usually must acquire recycled mills, often from breweries that have gone out of business.

|

Mash tuns, in which the ground malt is soaked in hot water to leach out the goodies. If I recall correctly, the far one is Balvenie's, and the nearer,

slightly bigger, is Kininvie's. Might have that backwards, though. Balvenie and Kininvie are both owned by the same family that owns Glenfiddich.

Kininvie was built in 1990 mainly to provide blending fodder, and to my knowledge has yet to be bottled as a single malt.

|

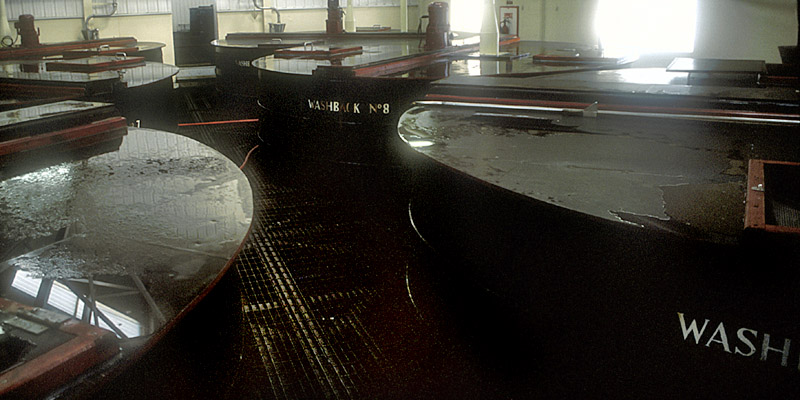

Balvenie's washbacks. Here the wort, the sweet liquid extracted in the mash tuns, is fermented. Yeast eat sugar and excrete alcohol and carbon dioxide.

(Yes, you drink yeast pee.) Up to this point, the process is almost identical to brewing beer, although the result here is typically 8-9% alcohol.

|

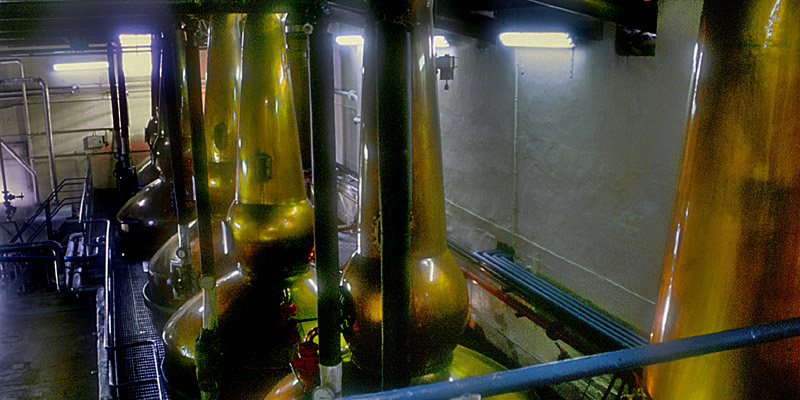

The Balvenie stillhouse. The wash produced in the washbacks is distilled in the wash stills, and the resulting low wines get a second distillation

in the spirit stills. The result is in the neighborhood of 70% alcohol, although it is usually reduced to 63.5% for maturation.

|

Barrels waiting to be filled--bourbon hogsheads, sherry butts, port pipes, and who knows what else.

|

One of Balvenie's warehouses, where the barrels sleep for ten years or more.

Next

| September | /Octoberrrrrrrrrrrr |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 |

The North Atlantic Arc Home

Mr Tattie Heid's Mileage

Results may vary

MrTattieHeid1954@gmail.com