from Saguenay to Øresund

26 August 2015

The North Atlantic Arc Home

| August | September | October |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | ||

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | ||||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

|

|

Wednesday 26 August 2015--Fjord is a Norwegian word for a long narrow

sea inlet. The geology community has adopted it to mean specifically a deep,

steep-sided inlet created by glaciation, as most of the Norwegian fjords were.

The Saguenay Fjord had its origins as a graben, the geological term for a zone

of collapsed land between two higher zones, formed by faulting. The Saguenay

graben was about 160 miles long. During the Ice Age, it was scoured by a vast

glacier, creating the basic contours of the current fjord. When the glacier

retreated, seawater filled the valley. The fjord itself, cutting through the ancient

rock of Charlevoix, is a little more than 60 miles long.

The Saguenay graben played a part in the catastrophic Saguenay Flood of 1996. An intense low pressure system over the center of the continent performed an enormous counterclockwise pirouette, picking up moisture over the Atlantic Ocean, before stalling over the Saguenay-Lac St Jean region. Over a period of 50 hours from July 19 to 21, an average of six inches of rain fell on ground already saturated by precipitation over the previous two weeks. More than eleven inches fell in the uplands to the west. The intensity of this was magnified by the funneling effect of the graben. But the real culprit in the disaster that ensued was the crazy quilt of dams, dikes, and reservoirs throughout the region, both public and private, most built many decades earlier to provide water and power for industry, many suffering from shoddy maintenance or outright neglect. The reservoirs were usually kept close to full in summer, and the various authorities were caught off-guard by the extraordinary intensity of rainfall. Opening floodgates at that point was too little too late; some could not be opened, anyway, jammed with sunken logs (remnants of log drives decades before), or simply inoperable after years of disuse. Overflowing reservoirs led to structural failure. A nearly forgotten dike at Lac Ha! Ha! gave way, and a wall of water roared down the valley, sweeping away much of downtown La Baie, which fortunately had been evacuated. Even the 35-ton vault of the Caisse Populaire Desjardins was lost, money and all. [According to Marc, it was never found; I haven't been able to corroborate that.] Numerous other watersheds suffered the same fate. This documentary posted on YouTube will give you some idea of the scope of the disaster across the region. It's truly mind-boggling. (The doc is in French, but you don't need to understand the words to get the picture.) The flood has had one positive effect, at least. Toxic runoff from industry in the area of Chicoutimi, long thought a nearly intractable problem, has been swept under the rug, so to speak, by a thick layer of fresh sediment deposited on the bottom of the Saguenay River and the Baie-du-Ha!-Ha!, obviating an expensive proposed dredging project. La Baie is where we go this morning, to board a cruise on the fjord. It's been almost twenty years since the flood, but the rebuilt downtown of La Baie still has that newish, not-quite-broken-in feel to it. Our vessel, La Marjolaine, departs at 10:00, heading out into the Baie-du-Ha!-Ha!. "Ha! Ha!" is evidently derived from a native word for a navigational cul-de-sac along a waterway; if you were traveling up the Saguenay and missed the sharp bend where the river enters the fjord, you would sail straight into this dead-end bay. It takes us the better part of an hour to clear the bay, and at 11:30 we are landing at Ste- Rose-du-Nord for an hour-and-a-half lunch break. The village of Ste-Rose-du-Nord sits on a small slice of fertile land that slopes relatively gently down to a small bay, nestled in amongst the cliffs. This was a productive pocket of farmland back in the day; now it seems to make its living as "the Pearl of the Fjord". I imagine that the several restaurants and casse-croûtes at the waterfront derive a large part of their income from the passengers of La Marjolaine, arriving daily in summer. Marc and I hustle up the hill to the restaurant Chez Mina instead. It's a small place, with a short menu--I have the tourtière de Saguenay--and the service is a bit brusque, but it's definitely a more authentic regional experience than burgers and poutine down by the pier. After lunch, there is time to stroll around the village, such as there is of it, and read some of the interpretation panels around, telling us about the ecology and human history of the area. I learn, among other things, that the fresh water flowing over the fjord from the rivers upstream is nearly opaque with runoff, and the dark saltwater depths are inhabited by Greenland sharks and many other peculiar forms of marine life normally found in arctic waters. The mix of fresh and salt currents is favorable for krill and plankton, which in turn draw whales to the mouth of the fjord. We will go looking for some in a few days. La Marjolaine pulls out of Ste-Rose at 1:00 and heads for the heart of the fjord. The rest of the trip is taken up with gawking, mostly. At one point, Marc expresses some disappointment that the fjord is not the narrow gorge the pamphlets and road signs seem to suggest [see the "Route du Fjord" highway sign at Saint-Siméon on yesterday's page], and I can understand that. But to some extent, it's a matter of acclimating yourself to the scale of things. Sailing down the middle of the fjord, one does not at first feel all that awestruck. But when the boat approaches the towering cliffs at one side or the other, the perspective changes completely, and preconceptions are forgotten. The fjord is wider than you thought it would be, but it's no less precipitous. The cliffs average nearly 500 feet and run as high as 1150 feet; the depth of the fjord averages almost 700 feet, and reaches a maximum of 890 feet. The land on either side is protected in the Saguenay Fjord National Park, established in 1983. In 1998, the waters of the fjord were included in the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park, along with a large swath of the St Lawrence estuary at the fjord's mouth. This is one of a small handful of Canadian parks that protect a purely marine environment, the first in Québec. If any further lesson on the scale of things is necessary, it is provided by Notre- Dame-du-Saguenay, a statue of the Virgin Mary standing on a promontory halfway up the cliff. That little white speck is nearly thirty feet tall. It was commissioned in 1881 by a traveling salesman named Charles-Napoléon Robitaille, in gratitude for deliverance from misadventure on the frozen river the previous winter. La Marjolaine pauses at a suitable viewing point while we are told the story, following which a recording of Ave Maria is played. The more jaded among us find this all a bit hokey, but it must be noted that some passengers are genuinely moved, even enraptured. La Marjolaine goes as far as Baie-Éternité, which we visited by land yesterday. The cliffs here are especially dramatic, and better appreciated from the water. Then we make the long run back to La Baie, landing at 5:30. We have dinner at La Voie Maltée (the Malty Way), a brewpub in a shopping plaza outside town. This is one of three Voies Maltées--Marc and I have been to the one in Quebec City. Then a nightcap at La Tour à Bières. Marc heads back to the room, and I take a stroll to the far end of downtown. We considered a room in a hotel down that way, and I want to see what we are missing. I find a broad plaza with a rhythmic fountain accompanied by colored lights and music...but hardly a human to be seen. There must be civic events here, on weekends, perhaps, but on a weeknight, this is the dead end of town, an urban ha! ha!. We chose well. Next |

|

La Baie

|

La Baie

|

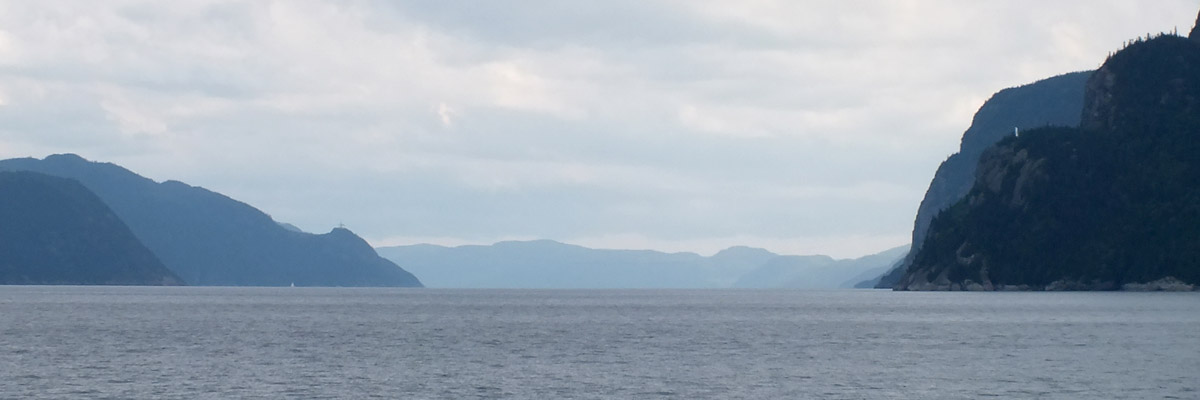

The Fjord Beckons

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Approaching Sainte-Rose-du-Nord

|

Sainte-Rose-du-Nord

|

Sainte-Rose-du-Nord

|

Sainte-Rose-du-Nord

|

Departing Sainte-Rose-du-Nord

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Annie 2012

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Notre-Dame-du-Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Notre-Dame-du-Saguenay

|

Seal

|

Seals

|

Notre-Dame-du-Saguenay

|

Notre-Dame-du-Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

Fjord du Saguenay

|

La Voie Maltée

|

La Voie Maltée

|

La Tour à Bières

|

Beautiful Downtown Chicoutimi

Next

| August | September | October |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | ||

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | ||||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

The North Atlantic Arc Home

Mr Tattie Heids Mileage

Results may vary