Friends In Three Countries

7 October 2017

The North Atlantic Arc Home

| September | /October/ | November |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | 1 |

|

|

Saturday 7 October 2017--At 1:55am on 23 January 1973, a volcanic

fissure opened on the hillside above Heimaey town. By 2:30, evacuation of the

5,300 inhabitants had begun, and within six hours it was largely complete. By

chance, stormy weather had kept the entire fishing fleet in the harbor, making a

maximum number of boats available. Over the next six months, workers fought to

save the island community as the eruption threatened to bury the town in lava

and ash. Seawater was sprayed on the advancing lava flow in an attempt to cool

and divert it from the town and the harbor. At one point, engineers thought they

might be able to save only one or the other, and asked the mayor which was more

important. "Without the harbor, what good is the town?" he replied. Fortunately,

the eruption subsided shortly thereafter. Nevertheless, 400 homes were lost,

and the town was covered with ash. Some residents never returned, but those

who did cleaned up, repaired, and rebuilt. The entrance to the harbor was

severely tightened, ironically making it a better, more sheltered harbor. Heimaey

lives yet, and is still one of the most important fishing ports in the country--I think

likely that the cod I buy in my local grocery is landed here. But the population of

the town has never returned to what it was before the eruption. Life goes

on...the trauma is left in the past, but not forgotten.

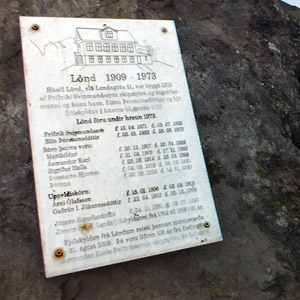

I take a walk this morning on a meandering trail on the long-cooled lava flow. Some former residents have placed plaques above their buried houses. Up near the eastern edge of the flow is the remnant of a geothermal plant. An experimental station, built not long after the eruption, used residual heat from the lava to provide hot water to a nearby neighborhood. In 1978, a full-scale plant was constructed, and eventually the entire town was connected. There was enough heat to serve the community for the next ten years. The town still uses a central boiler, which, according to an interpretation panel, runs on "surplus electricity". I assume a cable runs from a power plant on the mainland. Iceland seems to have more geothermal energy than it knows what to do with. Down by the narrow entrance to the harbor stands a replica of a Norwegian stave church, a gift from Norway to commemorate a thousand years of Christianity in Iceland, erected in 2000. Apparently the first Christian church in Iceland was built on Heimaey by Norwegians. I meet up with Marc and tell him I've found a good spot to take a photo over the town. He says he doesn't want to take any photos of the town, because it's ugly. I don't know whether to laugh or argue, and in the end say nothing. I understand what he means--it's a typically dour Nordic settlement, with architecture that ranges from dowdy to drab to depressing. The flat gray light does it no favors. From a hillside above, it looks like nothing so much as the landfill that isn't actually here. But it's not entirely charmless, and anyway, it's what's here, and I want to document it. It's just another way in which Marc and I think differently, despite which, I hasten to add, he is a perfectly agreeable traveling companion. We get in the car and drive south out of the town, past the airport and out onto Stórhöfði, a peninsula dangling in the cold Atlantic. There's a lighthouse here, and a view toward the southern islets, a couple of which appear to have cottages on them. Surtsey, the southernmost bit of land in Iceland, was formed by volcanic eruptions between 1963 and 1967, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, studied by scientists for insight into the ways that flora and fauna colonize new land. Stórhöfði is a huge tourist draw in summer, being a major nesting area for puffins. It's said that eight million of the birds inhabit Vestmannaeyjar in season, a mind-boggling number, nearly the human population of New York City. Not a one in sight now; they've been gone a month and a half, at least, to spend the winter at sea. Back in town, I visit Eldheimar, a museum built around a house buried in the 1973 eruption and excavated forty years later. The whole story of destruction, loss, and resurrection is told here. After, I walk up a trail to the summit of Eldfell, the volcano formed in the eruption. The surviving town is at my feet, to the right of it the lava flow that covered a third of it. I try to imagine streets and houses that once were there--no, still are, under the gnarled rock. We dine this evening at Gott, next door to the hostel. It's a relaxed and homey place--feels like eating in someone's front room. Brothers is quiet tonight, and there is time to contemplate our brief visit to a special place, and whether it would be worth fighting the tourist hordes to come in summer. It just might. Next |

|

Heimaey

|

Heimaey

|

Heimaey

|

Heimaey

|

|

|

|

Plaques

|

Stave Church

|

Harbor

|

Southern Islets From Stórhöfði

|

Southern Islets

|

Lighthouse On Stórhöfði

|

View North From Stórhöfði

|

Harbor

|

Heimaey

|

Eldheimar

|

Eldheimar

|

Eldheimar

|

|

Museum Photos

|

Heimaey

|

Heimaey

|

Climbing Eldfell

|

Eldfell

|

From Eldfell

|

Bjarnarey (pop 3)

|

Heimaey From Eldfell

|

Downtown Saturday Night

Around Heimaey

Next

| September | /October/ | November |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | 1 |

The North Atlantic Arc Home

Mr Tattie Heid's Mileage

Results may vary