Tuesday 5 November 2013--Our plan today is to circle Snæfellsnes, a

peninsula that is sometimes called "Iceland in Miniature". As best I can tell,

"Snæfellsnes" rhymes, more or less, with "rifle's mess"...although, truth to tell,

after hearing Icelanders speaking their native language, I'm quite sure that

nothing in Icelandic rhymes with anything in English, really. The two languages

have common Germanic origins--English through its Anglo-Saxon roots, and

Icelandic via Scandinavia--and it isn't difficult to find cognates. A loaf we

see in a bakery, for example, is labeled "sex korna braud"--six-corn (grain) bread.

But the two cousins have been a very long time apart.

We drive up over the pass at the base of the peninsula, from south to north, and

stop for a look at the town of Stykkishólmur. Had we made the trip to the West

Fjords, we'd have caught the ferry here. It's a pretty little town, smaller still than

Borgarnes, but very attractive. A night or two here might be nice.

Then it's off to the west, along the north shore. The peninsula is about fifty

miles long, with much mountainous scenery (notably the outlier Kirkjufell, "church

mountain"), and the towns of Grundarfjörður, Ólafsv k, and Hellissandur, none

with a population much over a thousand. At the latter, there is an outdoor

museum with sod houses and whale bones, among other things.

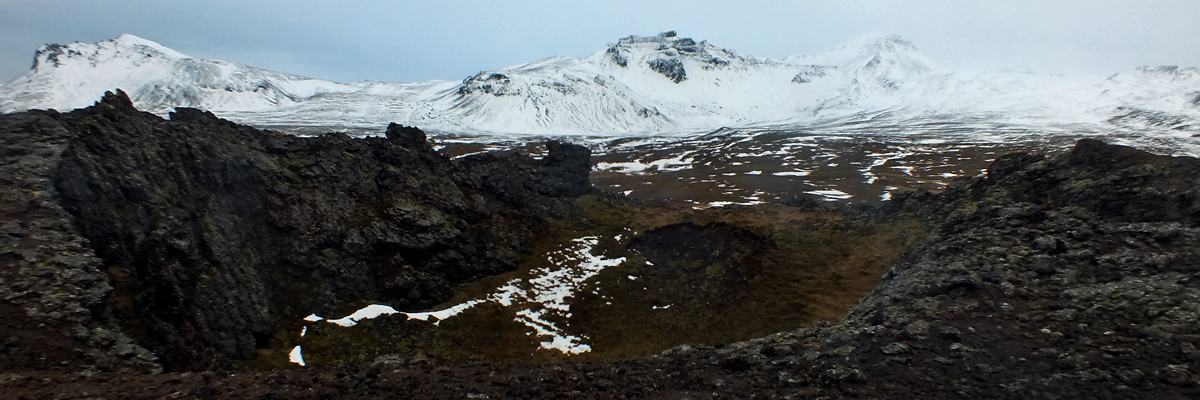

We turn the tip of the peninsula, rounding the mountain Snæfell and its glacier,

Snæfellsjökull. Jules Verne placed the portal to the center of the earth

somewhere on the mountain. Nearby, we examine Saxhóll, a small volcanic crater

similar to a few we saw on our first trip to Iceland in 1999.

The afternoon is getting along, so we motor along the south side of the

peninsula. Our one stop is, for me, the most important one of the day--

Laugarbrekka, the site of the farm where Guðríður Þorbjarnardóttir was born

around the year 980. Guðríður ("Gudrid" in English, usually) was probably the

most widely-traveled woman of the Middle Ages. Much of what is known about

her comes from the Greenland Saga and the Saga of Eirik the Red.

The Icelandic sagas are social histories of the tenth and eleventh centuries,

written in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, evidently after being passed

down as oral history. As such, they are not entirely reliable, and indeed

sometimes describe events (particularly supernatural ones) that are simply not

believable. Moreover, the two Vinland sagas contradict each other on many

details. They are probably, however, more rooted in fact than your average

Hollywood movie "based on a true story." Like many histories, they are

concerned for the most part with the actions of men. As little detail there is of

Guðríður's life, it's obvious that she was a remarkable woman.

Here are the bare bones of her story: Gudrid moved to the young Greenland

colony with her father and her husband, Thorir. Thorir shortly died of illness,

and Guðríður married Thorstein Eiriksson, youngest brother of Leif.

Together, they attempted a journey to Vinland to recover the body of

Thorvald, the middle brother, killed by skrælings (the local natives) on an earlier

trip. They were thwarted by weather, however, and shortly after their return

to Greenland, Thorstein fell ill and died. Gudrid then married Thorfinn Karlsefni,

a prosperous Icelandic merchant, and they were part of a large party that

attempted to establish a permanent settlement in Vinland. The colony didn't

last long, but Gudrid gave birth there to her son, Snorri, the first person of

European heritage to be born in the Americas.

Gudrid and Thorfinn returned to Greenland, then visited Norway before

resettling in Iceland. Thorfinn died shortly thereafter, leaving Gudrid a widow

for the third time. She converted to Christianity, became a nun, and made a

late-life pilgrimage to Rome. She lived out her life as a hermit in the convent she

founded on Thorfinn's estate.

The Vinland colony established by Leif Eiriksson and his followers was a

failure, but archeological evidence suggests that the Norse presence in North

America went on for several centuries, as the Greenlanders traded with the

Dorset people of Baffin Island, and harvested Labrador timber for treeless

Greenland and Iceland. The Greenland colony itself, which peaked at

something between 3,000 and 5,000 residents, dwindled and disappeared

sometime in the 15th century, at least in part because of a deteriorating climate.*

I first became aware of Guðríður Þorbjarnardóttir by reading the

novel The Sea Road, by the Scottish author Margaret Elphinstone. Guðríður's

pilgimage to Rome provides the framing for the story, as she tells a transcribing

monk about her life. The novel follows the sagas faithfully, their spare recitation

of events fleshed out and given life by Elphinstone. As in all of her novels, there

is a strong sense of geography, which is one reason she is a favorite of mine. I

know she researches both places and people at great depth, and don't doubt

that she has stood at Laugarbrekka, as Win and I are now.

We tromp over the site, examining the remains of a turf-built church, which was in

use as late as the 1880s. The remnants of the farmstead are nearby.

[You can read the Saga of Eirik the Red at the Icelandic Saga Database.

You can read the Greenland Saga, too, if your Icelandic or Old Norse are up

to it--it has yet to be translated into English there.]

The afternoon is fading, so we get in the car and hustle back to Reykjavík,

passing over Borgarfjörður and under Hvalfjörður. Arrive in town well after

dark, check into our hotel, and go for a pint at Micro Bar. Fall into chat with a

couple of Airwaves attendees, and tell them we'll be at Dillon Whiskey Bar

later. We say the same to a couple at Nora Magasin, where we have dinner.

Everyone shows up at Dillon, and we have a nice little going-away party.

Next

*Recent research suggests that the foundation of the Greenland colony's economy was trade in

walrus ivory, and collapse of that trade due to overhunting and increased competition from

elephant ivory may have been the main reason for the colony's abandonment.

|